- 2026

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

Effective Swabbing Techniques for Cleaning Validation

Searching for nothing would seem to be an absolute waste of time — unless you are responsible for cleaning validation. In that case, success is deliciously ironic since you can say, “I found nothing and that’s good news”.

Let's start from the beginning!

Those involved in the manufacture and quality control of pharmaceuticals and biotechnology products are aware of the need to prove that the production equipment and the manufacturing environment are sufficiently clean such that the next lot of product will not be contaminated by materials from the previous lot, i.e. that cross-contamination will not be an issue. The procedures and documentation for that proof constitute what is known as cleaning validation.

Cleaning validation can be considered a three-step process:

(I) the cleaning and rinsing of the requisite surfaces,

(II) sampling any drug or cleaning agent residues that might remain on those surfaces, and

(III) analyzing the sampled materials with the appropriate instrumentation.

Steps (I) and (II) are manual, sometimes tedious procedures, but only if they are done properly do they permit accurate results to be reported in step (III). We will look only at step (II) — the procedures that enable one to sample a cleaned surface with a high degree of reproducibility, to ensure that what is reported in step (III) truly represents the condition of the sampled surface.

Sampling Surfaces with Swabs

Assuming the surface is free of visible residue (i.e. that the cleaning stage is done), the challenge is now to sample that surface in a reproducible manner, such that any (invisible) residues, present in extremely small amounts, are collected and delivered to the instrument for measurement. The best type of swab or sampling is one with a head made of laundered polyester knit fabric (Figure 1) since that material provides the lowest levels of releasable particles, the highest recovery, and the lowest background when total organic carbon (TOC) measurements are employed as the analytical technique. To sample the surface, the swab is moistened then drawn across the surface in a thorough and reproducible manner to collect any residue into the interstices of the polyester knit fabric. The swab is then deposited into a suitable collection vial, then the residues are extracted from the swab head for subsequent analysis.

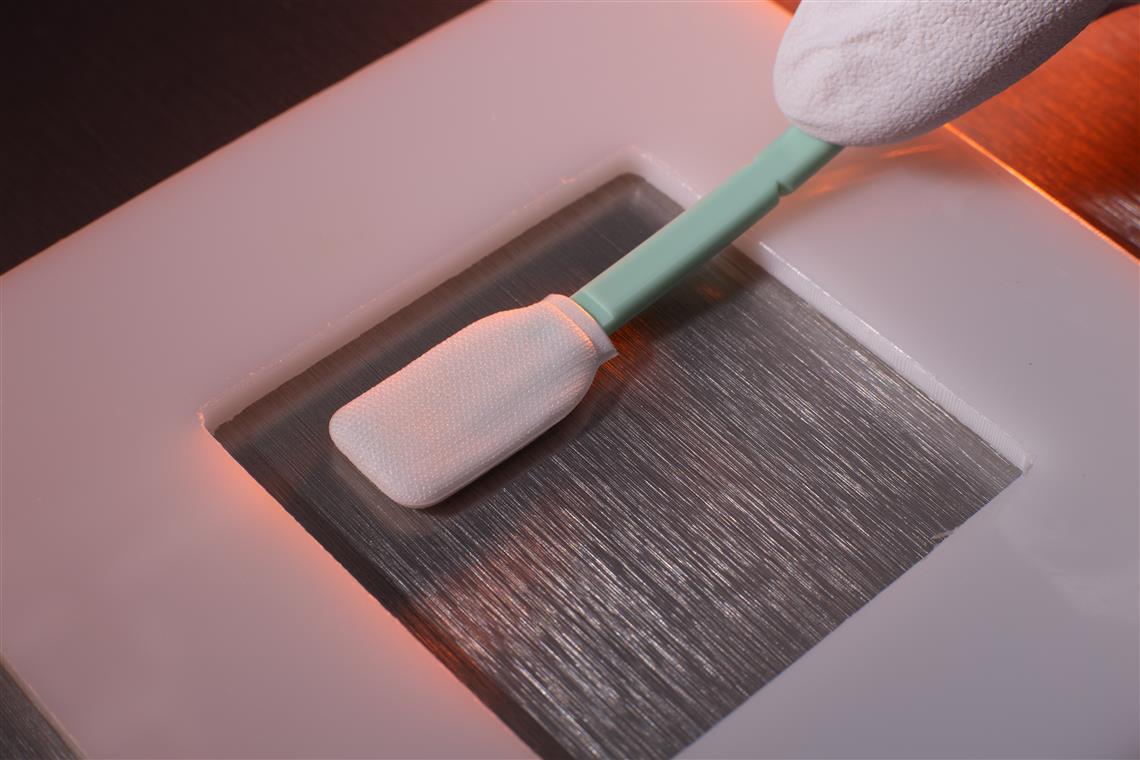

It is worth devoting a moment to the technique for moistening a swab since errors in the technique here will lead to inconsistent results. For best results, the swab should be damp, but not saturated. The degree of the moistness of the swab head (otherwise known as the percent wetting level) need not be identical from run to run, since residues will be picked up over a fairly wide range of swab head moistness. How the swab is used to sample the surface, i.e. the swabbing pattern, is critical to ensure accurate and reproducible collection of residues. For easily accessible surfaces, a template with a 5 cm x 5 cm opening can be used to sample the same surface area each time (Figure 2). As with wiping, linear overlapping strokes over the surface to be sampled will ensure that the residue is collected into the moist swab head.

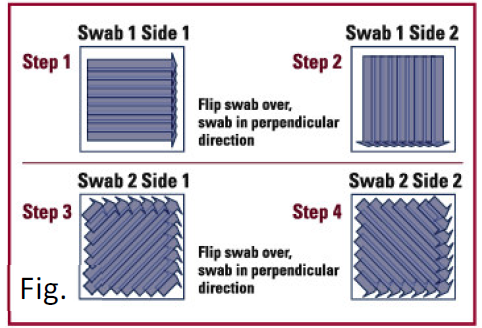

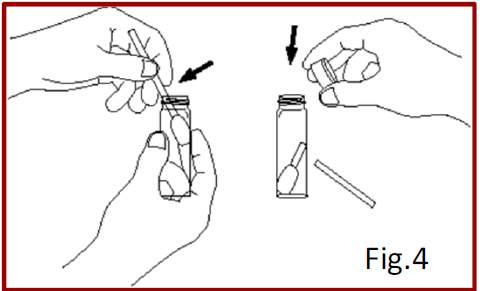

Figure 3 shows a typical sampling pattern employing 2 swabs. The first side of the first swab is swiped horizontally 10 times over the template opening, then the swab is flipped over and the second side is swiped vertically 10 times over the same surface. This swab is deposited into the collection vial (Figure 4). The first side of the second swab is swiped diagonally

upwards 10 times, then flipped over and the second side swiped diagonally downward 10 times. The second swab is deposited into the same collection vial. In this manner, the surface has been swabbed a total of 40 times, and here is a reasonable expectation that any residue on the surface has been transferred into the two swab heads. It is not always required to use two swabs; often one will do. Operators can verify that their technique for dampening the swab heads and swabbing surfaces is appropriate through replicate recovery experiments of known challenges dispensed onto sample surfaces. Ideally, one would like to recover 100% of the challenge, but recoveries may be limited to 75%-80%, depending on the sampling conditions and the residue. It must be recognized that the swab head may not get everything off the surface and that the extraction liquid may not get all of the residues out of the swab head. Indeed, a 90% efficiency at each stage, produces an overall recovery of only 81% (i.e. 0.9 x 0.9). Pre-cleaned vials and swabs are available commercially that provide TOC background levels of <10 ppb and <50 ppb TOC, respectively. This may be important if very low levels of residues are sought since one never wants to report at an analytical value obtained by subtracting two large numbers to produce a small difference.

Conclusions

So the search for nothing involves (i) good cleaning and rinsing protocols, (ii) proper swabbing techniques to ensure that any residues left on the surface are collected into the swab, and (iii) precleaned vials and swabs for minimum background levels. Rigorous attention to detail and technique will enable success in finding nothing.